Allan and I spent about an hour on the boat, listening to crew members talk about their journey, the boat, and Polynesian voyaging. It was an amazing opportunity and a wonderful experience.

We were disappointed not to see the sails unfurled. The boat was leaving the following day, but going only to Alert Bay, a very short trip from Port Hardy, so they didn't have to leave very early in the morning. We returned the day of their departure -- twice -- hoping to see the sails unfurled, but no joy. This image of the boat in full sail is from the Polynesian Voyaging Society. The rest of the photos are ours, courtesy of Allan.

As we walked down Port Hardy's Seagate Pier, the first thing we noticed is how tiny the boat is! Standing on the boat, you could feel it was very solid. It didn't move around under your feet the way an ordinary canoe or a tiny sailboat does. At the same time, it was mind-boggling to think that folks have sailed on the open ocean in this craft.

The majority of the Moananuiākea Journey is coastal, but in 1976 Polynesian voyagers sailed from Hawai'i to Tahiti on Hōkūle'a. The Hōkūle'a has also travelled to Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island), one of the most remote places on Earth. In doing so, the PVS disproved "drift theory," one of many anthropology ideas that viewed Indigenous people as helpless objects of the environment, rather than civilizations that constructed their worlds, as all civilizations do. (See also: aliens building the Pyramids and the Nasca Lines.) Part of the Moananuiākea journey will also be in open ocean.

The Hōkūle'a was constructed without nails or metal of any kind. It was built entirely by lashing ropes. Different ancient Polynesian peoples used different styles of lashing; the lashing on Hōkūle'a is a combination of different styles. More information about Hōkūle'a can be found here, and there's a diagram showing all of its parts here.

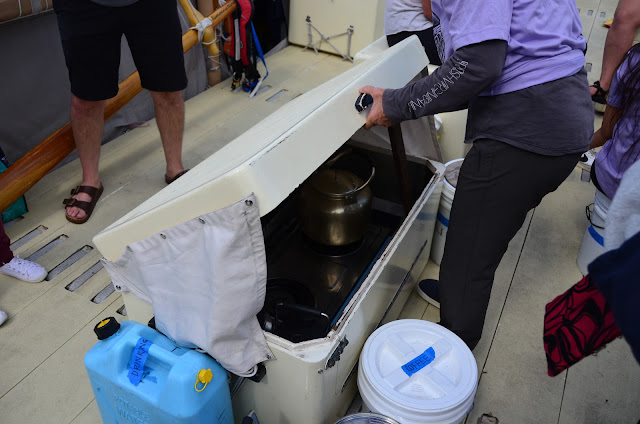

The boat's kitchen consists of two burners, that hide or pop out as needed. The crew eats mainly canned and dried food -- their chef performing magic to produce taste, variety and nutrition. The crew also fishes, and sometimes can purchase fresh fruit or eggs in a port. There is no refrigeration on board, so if they catch a lot of fish, it can be an issue! They oil eggs to make them stay fresher longer.

How does the crew go to the bathroom? Everyone wants to know! They strap themselves into a harness and hang off the side of the boat. And they use a buddy system for safety. As our guide said, "If you go overboard, you're like a coconut bobbing in the ocean."

The crew sleeps in shifts, in little hidey-holes.

Visitors took turns moving the huge rudder.

I was surprised to learn that the crew changes out every few weeks. Folks fly back to Hawai'i from wherever they are, and fresh crew members fly in to join the voyage. The navigators, with their more specialized knowledge, change much less frequently.

The Hōkūle'a is piloted almost entirely by traditional methods -- celestial navigation (i.e., using stars, especially the Sun), currents, types of waves, the colour of the water, bird sightings, and other ancient methods. An escort boat with GPS travels with them. There's great info about Polynesian wayfinding here on Hōkūle'a website.

When PVS was preparing for the 1976 Hawai'i-to-Tahiti expedition, celestial navigation had almost completely died out. There was only one person in the world who still possessed this knowledge, a Micronesian man named Mau Piailug. From Wikipedia:

Mau's Carolinian navigation system, which relies on navigational clues using the Sun and stars, winds and clouds, seas and swells, and birds and fish, was acquired through rote learning passed down through teachings in the oral tradition. He earned the title of master navigator (palu) by the age of eighteen, around the time the first American missionaries arrived in Satawal.

As he neared middle age, Mau grew concerned that the practice of navigation in Satawal would disappear as his people became acculturated to Western values. In the hope that the navigational tradition would be preserved for future generations, Mau shared his knowledge with the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS). With Mau's help, PVS used experimental archaeology to recreate and test lost Hawaiian navigational techniques on the Hōkūleʻa, a modern reconstruction of a double-hulled Hawaiian voyaging canoe.

Mau Pilau taught Polynesian wayfinding to Nainoa Thompson, now the long-time president of PVS. Thompson has navigated both the Hōkūleʻa and its sister canoe, the Hawaiʻiloa, from Hawaiʻi to other Polynesian island nations without using western instruments. He voyaged from Hawai'i to Tahiti solo in 1980.

More about Mau Pilau from Wikipedia.

The successful, non-instrument sailing of Hōkūleʻa to Tahiti in 1976 proved the efficacy of Mau's navigational system to the world. To academia, Mau's achievement provided evidence for intentional two-way voyaging throughout Oceania, supporting a hypothesis that explained the Asiatic origin of Polynesians.

The success of the Micronesian-Polynesian cultural exchange, symbolized by Hōkūleʻa, had an impact throughout the Pacific. It contributed to the emergence of the second Hawaiian cultural renaissance and to a revival of Polynesian navigation and canoe building in Hawaii, New Zealand, Rarotonga and Tahiti. It also sparked interest in traditional wayfinding on Mau's home island of Satawal. Later in life, Mau was respectfully known as a grandmaster navigator, and he was called "Papa Mau" by his friends with great reverence and affection. He received an honorary degree from the University of Hawaii, and he was honored by the Smithsonian Institution and the Bishop Museum for his contributions to maritime history. Mau's life and work was explored in several books and documentary films, and his legacy continues to be remembered and celebrated by the indigenous peoples of Oceania.

The principal mission of the Polynesian Voyaging Society is education, keeping the skills and their people's history alive.

This short video, featuring Nainoa Thompson, has some beautiful footage of Hōkūle'a on the sea.

This video, from local news in Hawai'i, talks about Polynesian Wayfinding.

Members of the crew were identifiable by their purple tees. They were so friendly and welcoming. It was an honour to connect with them.

4 comments:

The boat is 62 feet long.

I may have missed something, but is there a motor? Since the sails weren't up, I assume there is some other means of getting the boat to move. Oars?

There is no motor. The sails aren't up because the boat was stationary, moored to the pier. When the boat is in motion, the sails are up.

There are no oars, but there are paddles, used like the smaller kinds of canoes we are accustomed to seeing.

Thanks!

Post a Comment