If this frightens you -- if it fills you with dread, as it does for me, that your daughters will grow up with fewer rights than their mothers and grandmothers had, and that the use of their bodies will be dictated by legislators who have never met htem -- then, please remind them of history.By and large, Americans don't like learning history. They like learning propaganda. They enjoy stories that are exclusively about how America is great and always has been. Do not let your children believe in a fictitious, rosy version so the past where every woman was happily a mother. Tell them the true hsitory of this country, where abortion has always been commonly practiced.

And tell them your own history.

My greatest fear is not that abortion rights will be taken away in America. That is horrible. But that is already a reality for many people and has been for some time. It's that we will stop being angry about it. I am frightend that my daughter will grow up thinking her position as a second-class citizen, whose health and goals are less important to people in power than her capacity to breed, is normal and right. That she will think that this is just how things are.

5.29.2023

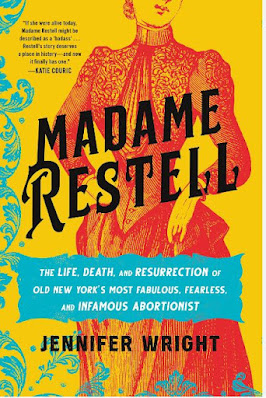

what i'm reading: madame restell (nonfiction version) (corrected and updated)

5.26.2023

twelve reasons i loved the pacific northwest labor history association conference

Through my union, I was extremely fortunate to attend the annual conference of the Pacific Northwest Labor History Association, this year held in Tacoma, Washington.

This was amazing timing for me, both logistically and in terms of my ongoing labour history self-education. Between labour book club, my own reading, and now this conference, I've recently absorbed a big chunk of learning, with overlapping and criss-crossing connections that are very satisfying.

I plan to write about the conference in more depth, but meanwhile thought I'd get some thoughts out in a listicle. As always in my lists, these are not in any particular order.

And so, twelve things I loved about the PNWLHA annual conference:

1. Synchronicity. The first book the labour book club read was The Cold Millions by Jess Walter. And the first event of the conference was an interview with two authors of historical fiction set in the Pacific Northwest: Karl Marlantes and Jess Walter. I was able to ask Jess Walter a question that came up in our group's discussion. How cool is that?

2. Radicalism. This was very much a gathering of labour activists outside of the structures and confines of unions. Opportunities like this allow us to explore a broader spectrum of possibilities, which we can then use to move our unions forward.

3. Belonging. As I said in 2009 when I attended the International Socialists' Marxism conference for the first time: this is my tribe. It's a powerful feeling to be among your own people, and it's soothing: an antidote for frustration and despair.

4. History. I believe the only way to understand where we are is by understanding where we came from and how we got here.

5. Local history. I was in high school when I learned that the main roads where I grew up in Rockland Country, New York, were originally traveled by Native Americans. I've been fascinated by local history -- wherever I am -- ever since.

6. Young workers! This was by far the most exciting event I attended: a panel of young labour activists. Of course I'm aware of the organizing going on in Amazon, Starbucks, and the fast-food industry -- but there is so much more -- and it so much better -- than I knew. I'll write more about this.

7. The keynote: "Reckoning with the Past to Move Forward". The keynote speaker was Moon-Ho Jung, a historian at the University of Washington. His speech was riveting, and set the radical tone for the day. More about this later, too.

8. The Washington State History Museum. The conference was held in this beautiful (but strange) building, and included admission and free time to see the exhibits. There was an exhibit by Japanese American artists called "Resilience -- a Sansei Sense of Legacy ," about Executive Order 9066; "Fine Lines," about cartooning; and a permanent collection. Interesting factoid: Lynda Barry, Gary Larson and Matt Groening all grew up in Washington State.

9. "Labor Wars of the Northwest". There was a screening of this documentary, which was great for someone like me who needs an overview. There was also some protest from PNWLHA members who claim the movie "is telling the boss' story," and want the organization to withdraw their association with the film. Although I didn't understand their cause, I appreciated that they were given a forum.

10. The IWW! The International Workers of the World are a constant theme in my reading and thinking. This conference was bursting with Wobby goodness.

11. Women. You can't talk about the IWW without highlighting the matriarchs of the movement. The courageous and outrageous organizing by women in labour was everywhere in this conference.

12. How history is constructed. Much of this conference, both overtly and indirectly, was about how history is written -- who writes the official stories, what sources are available to us, how we access other versions of our own histories. This is also linked to literacy, to a web of literacies that working people are often denied.

5.25.2023

tina turner, rest in power

She was a force of nature. A powerhouse. She had many lives, transcending all of the usual music-industry categories. We will all miss her.

Allan has a really nice tribute to her, with some great clips: here.

5.15.2023

in which a restaurant server protects my alone time and i am very grateful

The following day, before beginning a full day of programming, I decided to treat myself to a nice breakfast. So far on the trip I had been eating very light breakfasts in my room with food I had with me, and was looking forward to eggs, bacon, potatoes, the whole deal.

As I walked into the hotel restaurant, the server approached

me and asked, “Are you from Canada?” I was taken aback. She said, “The couple

over there wants to know if you want to join them for breakfast.” In an almost

empty restaurant, a senior couple was furiously waving hello.

Oh, no. No no no.

I reluctantly walked over to their table. “I guess you are here for the

conference?”

The server mouthed silently to me: “I’m sorry!” I tried

silently to convey “not your fault”.

So how did these people know I was Canadian? The previous

night, I attended the conference kick-off event: a historian interviewed two authors of historical fiction that take place in the Pacific

Northwest. One of the authors was Jess Walter, who wrote The Cold Millions

– the first book my labour book club read!

I had planned to ask Jess Walter a question, somethng that our group had discussed. I was called on first, and identified myself as a

librarian, union, here from Canada, and facilitating a labour book club. (Apparently this made me a

bit of a celebrity! Throughout the conference, people were greeting

me and asking about the LBC.)

So there I am at breakfast, pounced on before I sit down. I said politely, “I’m not very

social in the morning.”

The woman said, “That’s fine, you don’t have to be!”

Then

the two of them asked me questions for the entire length of breakfast. When

they weren’t forcing me to speak, they were chattering nonstop.

The woman told me that this annual conference is held in

three locations on a rotating basis: Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia.

The Canadian trustee has resigned, and they are looking for a replacement. "There’s nothing to it, it’s not much work at all.” Uh-huh.

Here comes the kicker.

The trustees are responsible for organizing the events. I

would be the only Canadian trustee, so it would my job to organize a

conference! This is the time I'm attending an event from this group -- previously I didn't know they existed -- and she is asking me to organize a conference! By myself! And

telling me it’s not much work! This is what my mother would call chutzpah.

She told me that after the conference, the group was having

its AGM and elections. I nodded politely, and said nothing. At some point I may

have said, “I work full-time and am active in my union. I’m not looking for

anything else to do.” But I doubt she was listening.

Fast-forward to the following morning. I tried again to have my quiet breakfast. The same server was there and she rushed over to me. “I’m so sorry! I didn’t know what else to do!”

She didn’t need to explain. I assured her: “It wasn’t your fault. What else could you do?”

She said, “I felt so bad for you! I heard you say ‘I’m not

very social in the morning,’ and she said ‘You don’t have to be’ – then talked

nonstop! Oh my god, I’m so sorry!”

She said she would seat me where no one could see me, and gave me a lovely table, near a window with a

view. She was still apologizing when she suddenly looked past me and said, “They’re here!

Don’t worry, I’m on it!” Then she rushed off.

A few minutes later she returned. “I seated them where they

can’t see you. There’s no way I’m letting them do this to you again! You deserve a quiet breakfast. Don't worry, I will protect you.”

Refilling my coffee, she said, “I felt so bad yesterday. I’m never letting anyone ruining someone’s alone time again.”

She fussed over me and made sure that every little thing about my breakfast was perfect.

It was so sweet.

While she was in the kitchen, I left her a ridiculously large tip and a scribbled thank you note. Then I walked quickly out of the restaurant with my head down.

5.12.2023

in which i finally visit the seattle central library and am completely blown away

For the BCGEU, I applied for and was selected to attend the Pacific Northwest Labor History Association's annual conference. (I was one of two BCGEU members who attended.) It was a fantastic conference. I plan to write a lot about it, but cannot do that just yet.

Instead, I will pick some low-hanging fruit from the trip to capture here. One of those is the Seattle Central Library.

* * * *

In Seattle, I met up with a longtime wmtc reader, the first time we had met in person. J is a kindred spirit, and he guided us on a very bookish tour of Seattle. We saw a beautiful Carnegie library, a university library that looks like a cathedral, and Ada's, an indie bookstore for techies, with an amazing cafe and just an awesome vibe. And possibly some other beauties that I may be forgetting.

Seattle booklovers recently enjoyed this independent bookstore bingo.

This was all very good. And it was lovely to see some of Seattle, with all its cafes and food and skyline and water.

But the Seattle Central Library is next-level. Library nirvana.

Previous to this trip, I had been to Seattle twice -- once in 1996 on our way to Alaska (including a ballgame at the hideous old Kingdome), and again on a west-coast baseball trip in 2002, at what was then called Safeco Field. The mammoth Central Library, designed to much fanfare by Rem Koolhaas, opened in 2004. (When it comes to ballpark competition, no city will ever top Seattle for Most Improved.)

Even though we're now on the west coast, Seattle hasn't yet figured into any of our travel plans. Plus I'm now a bit obsessed with Portland and plan to go whenever we can. But I will have to go back to Seattle to spend more time in this crazy wonderful library.

J said I was like a kid in a candy store. Perhaps a kid whose been deprived of sugar and all the candy is free.

First of all, it's huge. Eleven stories, 363,000 square feet of space, and a gazillion windows. (Actually 10,000 windows.)

And it has everything.

The best dedicated youth space I have ever seen.

A Children's Center that is separate, off to the side, so kids can make noise and be sheltered from adults. I was stunned by the size of both the space and the collection. All five of my library branches could fit in this Children's Center.

Massive amounts of public space for reading, studying, relaxing, working.

338 public computers. 338 public computers, yo!

An extensive research collection focusing on Seattle and the PNW.

Information booklets so beautifully designed that every public library should learn from them.

So much natural light, and views, views, views.

Just... so much.

Many people hate the building's design and shape, but I really like it. The colour schemes are weird, and I don't understand The Red Floor at all, but I appreciate the boldness. It is anything but bland.

If you're unfamiliar with the design, here's an image search. And another of the big, yellow escalator that was featured in every story when the library opened.

I had a couple of very brief exchanges with some library workers.

At the reference desk:

Me: "Is this a good place to work?"

They: "Uuuuyyyyeah... ummm... like any place, it has its pros and cons."

Me: "Are you union?"

They: "Yes, are you?"

Me: "Yes, I am."

They: "I think it's important."

Me: "Me, too."

In the Children's Centre, the librarian was practically glowing, a woman very obviously in love with her job.

I took only a few pictures, and only with my cell phone. The pics are nothing special, but I had to have them.

|

| Part of the teen space. |

|

| The sign shown in the photo above. |

|

| Dewey numbers on the Book Spiral |

Here are a few other cell-phone pics from the rest of our day.

The Suzzallo and Allen Libraries at the University of Washington, which locals call You-Dub.

|

| Sign at Ada's Cafe |

|

| "We filter coffee, not people." |

5.05.2023

the canoe family: reconciliation retreat

I'm in the middle of two amazing opportunities, one through my work, and one through my union. The work thing is complex -- and important.

Decolonizing the library: walking in two worlds

|

| Circle of Life, Trevor Hunt |

In 2019, BC became the first province to put the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) into law, with the Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA). We are very fortunate that the new leadership of our library system (more about that in the future) cares deeply about this responsibility, and is making it a priority.

The journey of decolonizing

All the institutions that make up our modern North American world are the products of colonialism.

Every institution -- educational, cultural, financial, judicial -- is built on colonial foundations, and work with colonial practices. In Canada these practices were, for a long time, hidden under myths of peacekeeping and multiculturalism. Canada appeared to be a benign and peace-loving nation, especially when compared with its blood-stained, racist neighbour to the south.

Now Canadians know better (or at least they should). When the truth about the so-called Residential Schools (i.e. concentration camps) came to light, those myths were stripped away. The brutality that was revealed was wholly at odds with Canadians' image of their country.

The profound and sustained response by vast numbers of Canadians gives me hope. Now it falls to us to understand how colonization has harmed Indigenous peoples, and how systems continue to harm all of us.

I say "all of us" because (as I've written about in many different contexts) exclusion and inequality harms both sides, the oppressor as well as the oppressed. Never to the same extent, of course. But a divided world benefits only the ruling class, and even that, not very well.

When we begin to see the our world through a decolonizing lens -- when we make the structures visible -- we can gradually begin to remake them. And, whenever possible, we can intentionally embed Indigenous worldviews and ways of knowing into our systems.

This work will always be imperfect and always incomplete, but we cannot use that as an excuse for inaction.

Our guides in this journey speak about “walking in two worlds". That describes the ultimate goal: to think, reflect, and incorporate Indigenous ways of being and knowing into our present systems.

That’s a lot of words, and if you don’t know what it means, you have a lot of company. Not so long ago, I didn’t know what it meant, either. Understanding has come to me gradually, over years, as I read, watch, listen, and explore. This week my understanding made a big leap forward.

Decolonizing our library

I have the amazing good fortune to be part of a team whose purpose is to guide the Vancouver Island Regional Library on this journey. Each person on the team lives and works in a different geographic region of the VIRL service area, which is associated with one or more Indigenous Nations, usually several Nations that make up a language group or family group.

I should emphasize that hundreds of VIRL staff care deeply about Reconciliation. This team is just a fortunate few who are geographically diverse, passionate about this work, and were invited to participate.

VIRL has hired a consulting team to help guide the journey: Toro Marketing. Toro are two women with deep connections with several Indigenous communities, and a lot of experience in this work.

After a series of online meetings, it was decided that our team would meet in person to create the Reconciliation framework. When I confessed to another librarian on the team that I really had no idea what that meant – what we were actually going to do – I learned I was not the only one.

Going into this retreat, all we knew was: we are excited about this work; we believe in its importance; we are approaching it with openness, curiosity, and honesty. For me this means checking my cynicism and pessimism. I can acknowledge that sometimes I have those feelings, but I will consciously put them aside, and approach the work with optimism and hope.

The Wildwood retreat: day one

The retreat was held in an incredibly beautiful natural setting, in the Wildwood Ecoforest, outside the town of Ladysmith. We were guests of both Toro and members of the Stz’uminus and Snuneymuxw Coast Salish First Nations, including a hereditary chief.

On the first day, we sat on seats and benches around a fire, and mostly listened and observed. There was beautiful singing, and drumming, and stories – both individual stories of trauma and recovery, and discovering and claiming identity, and also sacred stories. Some of the people around the fire were related by blood and birth, others were people invited into the Nation -- adopted, so to speak.

While we listened, one young man was preparing salmon to be cooked in the traditional way on the fire. (My photos from another, similar salmon meal are here.)

Many of the stories were intensely moving. Many were fascinating and felt like a privileged glimpse into another world.

The First Nations people among us all expressed thankfulness and gratitude towards us. It was a bit overwhelming. We all enjoy such privilege, and the original inhabitants of this land have lived through a genocide. Yet they are thanking us! I felt wholly undeserving of this; we all did. But it was clear that their thanks and respect were completely genuine.

We enjoyed a lovely simple luncheon that some community members made, and we spent some time walking the beautiful land.

Land-based learning. Life is a circle.

Indigenous ways of knowing and learning are always connected to the land. "The land" is what we non-Indigenous people call "nature".

Indigenous beliefs teach that the land is alive – from the tops of the mountains to the bottom of the sea -- and that all life is interconnected. And if we can quiet our minds and approach the land with respect and openness, we will learn. Conversely, it is believed that many (or even most) of the world's problems derive for disconnection with the land, and from living wholly disconnected from the Earth.

(I’m saying this very poorly. My understanding of this grows all the time, but not to the extent that I can easily explain it.)

There are hundreds, thousands of Indigenous nations, each with its own language, traditions, culture, and histories. Yet there are some commonalities among all Indigenous cultures of the Americas, and throughout the world. One such commonality is a worldview of connectedness -- a respect for all beings (including things we may not regard as beings, such as rocks, water, air, and mountains), and the belief that all beings are connected with each other, and all are sacred.

Indigenous belief systems see humans' place on the land (in nature) differently than western and Judeo-Christian culture. Living creatures are not divided into a hierarchy, with humans on top. Humans are not superior, and do not have “dominion over” other life. Rather, life is a circle, or a web. All are connected, all our related. This worldview is found in every known current and past Indigenous culture.

Brushing ceremony

Towards the end of the day, we participated in a Coast Salish brushing ceremony.

Every Indigenous nation has some type of cleansing ritual (some of which have been appropriated into New Age and other spiritual practices). Many people are familiar with smudging, which may involve the ritual burning of sage or sweetgrass.

Stz’uminus and Snuneymuxw people perform brushing, using the tree that is central to their lives -- the cedar.

People sang, drummed, and chanted, as each of us took a turn standing and having our bodies, head to toe, brushed with cedar fronds. It was very intense, and also very calming and relaxing, at the same time. You can see videos of some cedar brushing ceremonies here.

This first day, we just listened. We did introduce ourselves and shared briefly where we live and work, and a bit about our motivations for this work. But mostly we listened.

The library people all stayed in a hotel in Nanaimo, and were shuttled back and forth by a local person with a transportation business -- Janie's Got a Bus. At the close of the day, we walked back through the woods, met our shuttle, and went to our hotel, exhausted.

The Wildwood retreat: day two

The following day we spent working in the lodge.

The lodge is one of those gorgeous buildings that I think of as "rustic elegance," all hewn wood and stone, huge windows overlooking the forest and river, natural light pouring in.

We sat in a circle -- the executive director, librarians, managers, and a library assistant -- and the consultants guided us through a process of creating a framework.

Here is one of the tools we used. This was created by Laura Tait, an Indigenous educator, for use in schools. We are adapting it to the library system.

Many questions, some answers, and a very, very long timeline

There were many decisions to be made and points to be discussed.

Where are we individually, and where is the organization as a whole? Do we assess those at the same time on two parallel courses, or do we assess each separately? How and when do we bring along all the other employees of the organization? How can we incorporate decolonization into every facet of the organization – into finance, purchasing, hiring practices, facilities maintenance? What would true decolonization of public services look like?

How do we support people who are just beginning their journey -- and how do we approach people who want no part in this? What resources do we need to continue our journeys?

Many questions, much discussion. Some consensus, some open questions.

One thing we keep coming back to is approaching this work itself from a decolonizing lens, a meta discussion if you will. In our library work -- in most work in the so-called western world -- there are agendas, checklists, deadlines. We check off a task and move on to the next. Decolonizing means putting all that aside. Reconciliation is not a checklist to be conquered. It is ongoing work, work that never really ends. This work is all process. All journey. Never finished.

It helps me to think of decolonizing the way I think about being a writer, or being a librarian, or trying to be a better version of myself. That work is never complete. It is always becoming. And the work is not linear. It doesn't happen in clearly defined steps. It often develops in ways we cannot anticipate.

So when we look at that rubric, above, we are likely in many places on that grid at the same time. And we'll each move through the grid at different paces and in different ways. But one thing we know: this work is not optional. This will be mandatory work for every library employee.

In the lodge, we had another simple and abundant lunch, and continued in the afternoon, deciding our next steps. Another walk through the woods to the shuttle, then dinner and drinks at a local pub. Then back to our hotel rooms.

The Wildwood retreat: day three and final

The third and final day, our two guides and the elder came to the hotel.

We shared breakfast and a benediction, and we listened to more beautiful stories. Again, the Indigenous elder thanked us, telling us that working with us has helped him be in touch with his best self, and expressed gratitude for our journeys. All three spoke of this work as being grounded in love.

We took turns expressing our thanks and gratitude in return. We were all very emotional.

Two notes of interest

One of our guides said, "You will hear a word, one that is likely to make you uncomfortable. It’s a word we keep out of our schools and libraries: prayer. Here, we use the word prayer because it’s the closest word we can find for a concept that has no English word. These prayers have nothing to do with religion. This is absolutely not a religion. This is a way of seeing and knowing about life and all living things."

Again, I cannot do this justice. All I can say is that I am a hardcore atheist, but I am comfortable acknowledging and accepting the worldview I am being shown. It actually fits very nicely with my own belief systems.

Then there is the name of our group. I have been calling us the Reconciliation Team. I like the word team, and use it often in both work and union. But I was the only one who liked the word!

Our three guides said we are family.

Later, at the pub, I said, "I'm going out on a limb here, but am I the only one who is not comfortable calling us family?" And I was! The only one!

Someone went into an explanation of a broader concept of family. Well, yeah. I'm no stranger to that. But this group is not family in any sense. We have much respect and admiration and affection for each other. But family? To me that feels forced.

Others said that as we do this work together, we will become family. I'm not even sure about that. But I won't belabor the point.

On our last day, during the closing ceremonies, someone in our group thought of our name: the VIRL Canoe Family. All VIRL branches are on or near water. All coastal Indigenous people use canoes. We are on a journey. It's brilliant.

Pronunciation guide: First Voices

One last note here. If you are interested in learning how to pronounce words of a specific Indigenous language, YouTube and the internet in general are terrible. Often someone (maybe a bot) is just reading the word phonetically.

Some of the sounds are very difficult for English speakers to learn. Others are fairly straightforward. But sounding out the word phonetically will not help.

The best resource for correct pronunciations is the First Voices Language Archives. The site links to 75 different language websites. If you're interested in learning, a good place to start is with a greeting, or a word of thanks and appreciation. Often one word will be used for all three. One of the first things I learned at the Port Hardy Library was Gilakas'la.

.jpg)