I'd be willing to bet my paycheque that Bruce Watson, author of

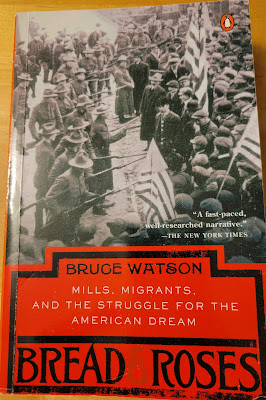

Bread & Roses: Mills, Migrants, and the Struggle for the American Dream, did not want his book to have that title.

The 1912 millworker strike in the city of Lawrence, Massachusetts is now referred to as "the Bread & Roses strike" -- but it was never called that in its time. In fact, the misnomer became associated with the strike (despite what Wikipedia claims) only in the 1980s!

Watson addresses this oddity in the book's introduction as well as in the epilogue. Having read his impeccably researched account of the strike -- and knowing what I do about publishers, and the compromises writers must make to be published -- I can all but guarantee this author did not want this title.*

This book has been on my List since it came out in 2005, and I found a copy on my recent trip to Powell's in Portland. I'm so glad I did! It was riveting.

The story of the 1912 Lawrence textile worker strike is easy to love. 20,000 workers from all levels of mill work -- immigrants from 51 different countries who spoke at least 12 different languages -- had had enough.

They lived in abysmal conditions. Their work was dangerous, and the machines were constantly sped up, causing the inevitable, hideous accidents and deaths.

They ranged from tall twelve-year-olds whose forged working papers claimed they were fourteen to men and women approaching fifty. Some were slightly older, but not many lasted that long in the mills. Inhaling fibers that floated through the dank, humid mill rooms, a third died within a decade on the job. Malnourished, they succumbed to tuberculosis, pneumonia, or anthrax, known as "the woolsorter's disease." They were crushed by machinery, mangled by looms and spinners. In a single five-year span, the Pacific Mill had a thousand accidents, two for every three days on the job. Those who avoided accident or disease just wore out like an old suit. Doctors and ministers in Lawrence lived an average of sixty-five years. Mill bosses could expect to live fifty-eight years. The typical mill worker died at thirty-nine.

They had enough. They united. They walked out.

They stood strong against national and ethnic divisions that had been used to divide them.

They stood strong against hunger and the freezing New England winter, pooling resources to create a soup kitchen -- something entirely new at the time.

The state militia was brought in, threatening the strikers with bayonets, beating them, and causing at least one death. The workers stood strong.

Their leaders were jailed. The workers stood strong.

At one point they were offered a tiny raise. They had the courage to reject it, and stayed out, knowing that the owners were beginning to crack.

They created a democratic strike, making decisions cooperatively, and a joyous one, parading around the city, singing.

They employed some brilliant tactics, sending their malnourished children to New York City and Boston to live with host families, for the children's health and safety -- and also for propaganda. Congressional hearings into conditions in the mills were held, and the muckraking press made sure that their stories of poverty and hardship were told.

Bread & Roses is a richly detailed book, but it's never boring and rarely bogged down. Watson created so much tension and suspense that I started to wonder, am I totally wrong about this? Did they not win?

But they did win. And what a win it was.

The striking millworkers won major pay increases, with those at the bottom tier of the pay scale getting the largest percentage increase, as much as 20%. Beyond wages, they won at least a portion of every demand, compromising on amounts, but getting their foot in the door on entirely new concepts.

And beyond that: they changed the labour landscape of an entire industry.

All along the rivers of New England, wherever mills had tapped the power of flowing water, fear of another Lawrence inspired sudden wage increases. On Saturday afternoon [only hours after a settlement was reached in Lawrence], mill owners meeting in Boston granted increases of 5 to 7 percent to 125,000 workers. The mill men caved in, one lamented, like "a row of bricks, one falling and knocking down all the others." Some boosted wages without even being asked, other to settle strikes in the making. All that coming week, the bricks fell. In North Adams, Massachusetts. In Greenville, New Hampshire. In Providence, Rhode Island. In Biddeford, Maine. They even knocked over the toughest textile town of all, Fall River, Massachusetts. By the time the last brick fell, some 300,000 workers had seen their wages rise thanks to the strikers in Lawrence. The raises would put ten to twelve million dollars into textile workers' pockets in the coming year, yet in mills that granted less than those in Lawrence, they would also stir a demand for parity, leading to copycat strikes.

This brought tears to my eyes. This is the dream: that workers rising will benefit all. And it was realized.

This was also an easy story for me to love, as it features the IWW (the organization that comes closest to representing my beliefs and worldview) and the radical luminaries Big Bill Haywood and Helen Gurley Flynn. There are cameos by Margaret Sanger, Ida Tarbell, and Emma Goldman.

But although I love Haywood and "Gurley," as she was called, the activists I encountered for the first time in Bread & Roses were even more interesting. Joe Ettor, the IWW organizer, led the strike with an uncanny mix of toughness and empathy, democracy and strong leadership. I was in awe of him; his name should be a household word among students of labour history. Arturo Giovannitti -- worker, poet, editor, organizer -- was another fascinating and endearing figure. Both men were arrested, falsely accused of murder, and jailed.

When at last the workers jammed the union hall to vote on the deal, the terms were read out in Arabic, Armenian, French, German, Greek, Italian, Latvian, Polish, and Yiddish. They sang songs of victory and solidarity for hours. They even voted to take a few days off before going back to work.

When it was all over, Haywood addressed the crowd.

You, the strikers of Lawrence, have won the most signal victory of any body of organized working men in the world. You have won the strike for yourselves and by your strike you have won an increase in wages for over 250,000 other textile workers in the vicinity, and that means in the aggregate millions of dollars a year. . . . You are the heart and soul of the working class. Single-handed you are helpless, but united you can win everything. You have won over the opposed power of the city, state, and national administrations, against the opposition of the combined forces of capitalism, in face of the armed forces. You have won by your solidarity and brains and muscle.

-------------------------

* A similar painful re-titling happened to my partner, about his book about the 1918 Red Sox. In fact many things about Bread and Roses reminds me of Allan's book.